Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD)

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a common eye disease that can blur the sharp, central vision that you need for activities like reading and driving. As the name suggests, AMD is most common in people over 60, and more people are suffering from AMD as the population ages.

What is age-related macular degeneration (AMD)?

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a progressive eye condition that causes damage to the macula, a small area of the retina that is responsible for central vision. Over time, the center of your vision may become blurry or wavy, making it difficult to do things that require sharp vision such as reading, driving, and recognizing faces.

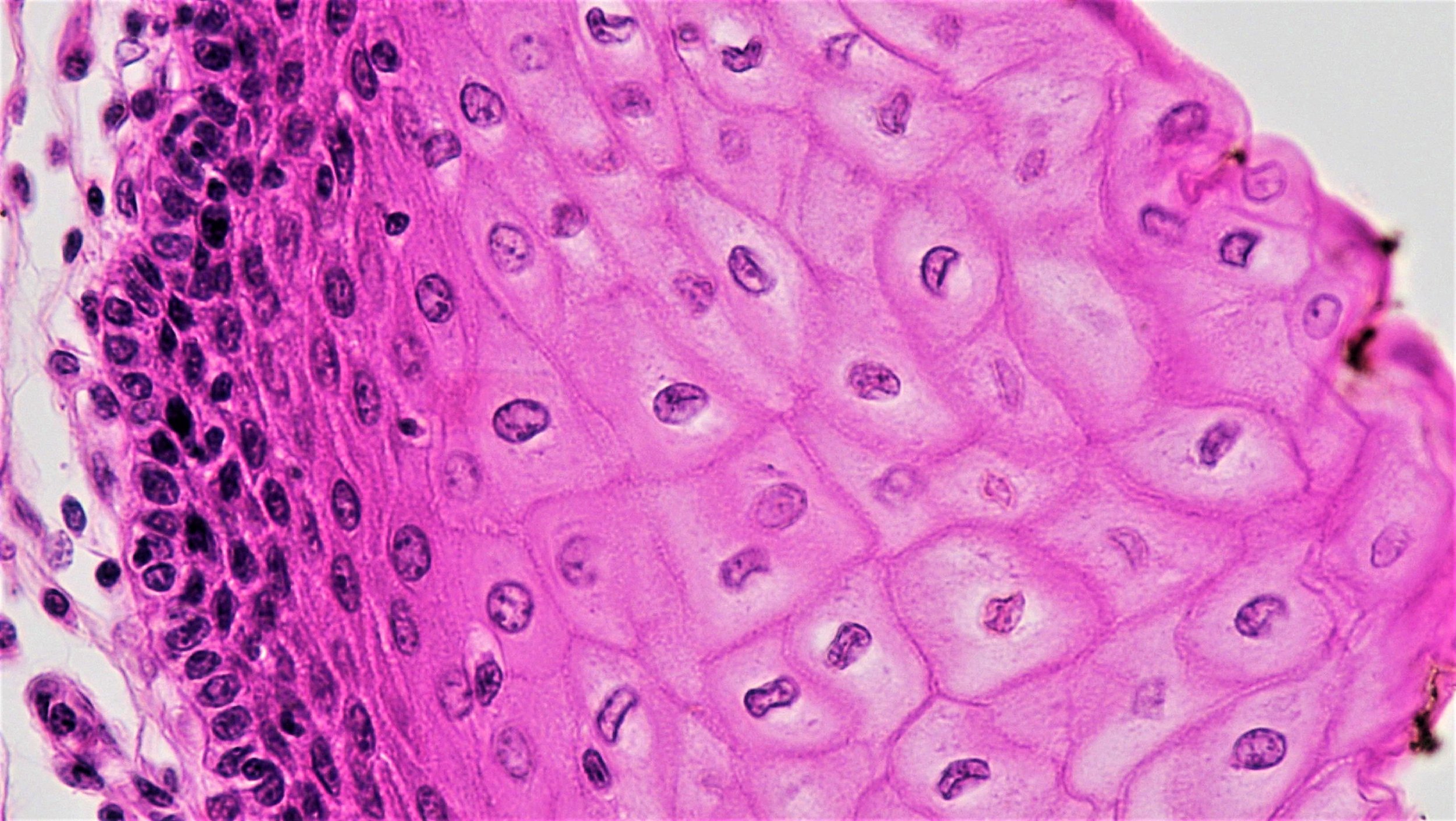

The macula is a small area of nerve tissue, about 5.5 millimeters in diameter, located at the back of the retina that is responsible for central vision. It is densely packed with photoreceptor cells called rods and cones that transmit the light from the retina via electrical nerve impulses to the optic nerve and into the brain. These photoreceptors are supported by an adjacent layer of cells called the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), which support the rods and cones by delivering nutrients from the bloodstream and removing waste that the rods and cones generate. AMD develops from damage to and progressive loss of the RPE. There are two types of AMD, the dry form, and the wet form.

In AMD, the RPE cells stop performing their support functions and the rods and cones die, resulting in a loss of central vision. Dry AMD typically progresses over several years. In the less common wet AMD, central vision can be lost in a matter of weeks or days.

Dry AMD

In dry AMD (also known as geographic atrophy) small deposits, called drusen, accumulate under the retina. Over time, the RPE cell layer near the macula is damaged which in turn leads to a gradual breakdown of the rods and cones. These changes cause central vision loss.

Wet AMD

In wet AMD (also called neovascular AMD), abnormal blood vessels grow underneath the retina and macula. This process is called choroid neovascularization (CNV). These new vessels are fragile and often leak fluid and blood into the layers of the retina. This can cause swelling or scarring and stop the RPE cells from functioning. The damage may be rapid and severe.

How is AMD treated?

Dry AMD

There is currently no good treatment for the dry form of AMD. Patients are encouraged to support general eye health through a diet rich in leafy green vegetables, nuts, and fish and, as the condition advances, to supplement their diet with key vitamins and minerals. See related recommendations from the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

Wet AMD

For wet AMD, doctors use drug treatments and surgical techniques to help preserve existing vision. The current first-line treatment is the injection of a drug into the affected eye to inhibit the formation of new blood vessels. These drugs block the production of vascular endothelial growth factor, or VEGF, that signals the body to make new vessels. For many people, the injections need to be repeated every four-to-six weeks.

For some types of wet AMD, various laser surgeries may also be used to remove or reduce the number of vessels or to seal them and slow their leaking. Unfortunately, even the most successful treatments do not necessarily prevent new vessels from forming or the repaired vessels from leaking again. In addition, the surgery can cause scarring or further damage the nearby RPE cells.

How are we using stem cells to understand AMD?

Scientists are using stem cell research to better understand the cells in the eye and how they become diseased, to make cells that could replace damaged cells in the eye, and to identify new drugs that could treat AMD.

To understand the cells in the eye and how they become diseased. Scientists study stem cells in the lab to help them understand how the different cell types in the retina develop and function together, which has led to more sophisticated ways to model normal eye development in the lab and to understand how healthy eye tissue becomes diseased.

To make cells that could replace damaged cells in the eye. Scientists are exploring ways to use stem cells to replace the cells lost in AMD. In both wet and dry AMD, the RPE layer that supports the function of rod and cone photoreceptors is damaged. Stem cell researchers are working on ways to replace the damaged RPE layer with lab-made RPE cells, which they believe will halt or even reverse the vision loss associated with AMD. Scientists are also working to replace the photoreceptor cells (rods and cones) themselves.

Replacing rods and cones is challenging, because these cells have to establish connections with nerve fibers that feed signals into the optic nerve, which sends those signals to the brain to interpret. Researchers are actively working on this approach, but ensuring new rods and cones integrate properly with existing nerve fibers alongside the patient’s existing rods and cones after transplant is very complex.

PE cells, in contrast, don’t need to connect with nerve fibers, so getting them to integrate with existing retinal cells may be easier. New RPE cells could replace diseased RPE cells and take on some of their supportive functions. If the transplant is done before rods and cones have been lost, new RPE cells may be able to prevent them from dying, thus improving central vision, or at least stopping the progression of the disease.

To identify new drugs that could treat AMD. In addition, stem cells are being used to identify new drug treatments. Healthy, stem cell-derived RPE cells can be stressed to produce abnormal cells that display features of AMD. These cells can be grown in the lab and studied to better understand how AMD progresses, which may lead to earlier detection and better prognosis. The cells can also be used to screen potential drugs for safety and effectiveness.

Stem cells are also being used in drug discovery. Healthy RPE cells can be stressed to produce abnormal cells that display features of AMD. These cells can be grown in the lab and studied to better understand how AMD progresses, which may lead to earlier detection and better diagnosis. The cells can also be used to screen potential drugs for safety and effectiveness.

What is the potential for stem cells to treat AMD?

Researchers are taking several approaches to make RPE cells for transplantation. They are trying different cell sources and different ways to deliver the cells to the eye. Longer term, as more is known about how different cell types in the eye develop and techniques to generate rods and cones are improved, researchers hope to replace rods and cones in conjunction with the RPE cells.

Making replacement RPE cells:

Some researchers are using induced pluripotent stem cells to grow RPE cells. Induced pluripotent stem cells are made from skin or blood cells that are manipulated in the lab to become stem cells that can form any cell in the body. Induced pluripotent stem cells can even be made from the patient themselves to reduce the chance of rejection by the immune system upon transplantation. And to speed this process up, researchers are working on ways to take a patient’s skin or blood cells and transform them directly into RPE cells.

Other groups are using other types of stem cells such as human embryonic stem cells, or stem cells derived from the RPE. These RPE-specific stem cells can be grown from the adult RPE, for example, from eyes donated to eye banks.

Delivery to the eye:

Researchers are exploring different methods to deliver the replacement RPE cells to the eye, including creating patches of RPE cells in the lab. In one approach, a one-cell-thick layer of RPE cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells, human embryonic stem cells, or adult RPE stem cells is implanted in the eye. In animal tests, these “patches” have shown promise; the RPE cells appear to be stable and don’t migrate to other areas of the eye.

Another way the cells can be delivered is as a suspension of cells, which is injected into the eye under the retina. The cells, derived from induced pluripotent stem cells, human embryonic stem cells, or RPE stem cells are grown and differentiated in the lab into RPE, then placed in fluid and injected. This approach may be less invasive.

For both approaches, a critical question is whether these cells will integrate well with the patient’s own RPE cells and do their job of nourishing the rods and cones over the long term.

Special Attributes of the Eye

The eye is a good target for stem cell treatments. It is relatively self-contained, with many barriers that keep cells from migrating to other parts of the body. It is easy to assess the effectiveness of treatments in the eye because researchers have tools for viewing the eye’s interior and for measuring its visual function. They are also able to compare results from a treated eye to an untreated eye in the same patient.

What is the clinical status of cell-based therapies for AMD?

There are now several early-phase clinical trials planned or underway to test different approaches to generate and deliver lab-made RPE cells to the retina to treat AMD. Some of these trials have been in patients for dry AMD, others in wet AMD.

For each strategy, initial trials are primarily testing whether the different approaches are feasible and can be done safely. To date, these studies include only very small numbers of people. The first reports available from some of these trials have been encouraging—the cells have been well-tolerated, and participants’ vision has not deteriorated and, in some cases, has improved at least in the short term.

Physician-scientists are continuing to track progress over time and are gaining a better understanding of how the new RPE cells interact with the existing tissue in each of dry and wet AMD. They are expanding trials to include more people and to determine how beneficial the RPE cell treatment will be.

Concerns

Despite progress and encouraging clinical trial results, cell-based treatments for eye conditions are still experimental. There is much more that needs to be learned about different treatment approaches and whether they will be effective.

Unfortunately, there are clinics selling unproven cell “therapies” or offering them as part of a clinical “study” outside of appropriate regulatory oversight. These clinics often make claims that are not backed up by facts. Before considering a cell-based treatment for AMD, even a clinical study or trial, take the time to learn more:

Read more about what eye specialists recommend.

Read other pages on this website to learn about red flags, such as high costs, and things to consider when thinking about participating in a clinical trial.

Useful Links

March 2019