Chimeras

Chimeras are persons or animals that have some living cells in their body that came from another person or animal. Chimerism can occur in nature (for example a mother’s cells can be found in her child decades later, just as a child’s cells can remain in their mother); can result from transplants (such as human-to-human organ transplants); or chimeric animals can be created in the lab for use in biomedical research.

How are chimeras used in research?

While non-chimeric animals have been successfully used to model various human diseases, they cannot always replicate the human condition. The ability to more accurately model human diseases within a laboratory setting can greatly help researchers in discovering disease processes and treatments that otherwise might not be found. Human-animal chimeras have been used for decades to better approximate how the human body works and identify new treatments for various diseases.

In the 1960s, scientists conducted pioneering work transplanting quail cells into a developing chick embryo. This work provided groundbreaking insights into how cells contribute to specific systems, tissues, and structures and went on to help inform our understanding of brain development, epilepsy, and other disorders. Now, there are many different types of research that involve chimeras as a way of studying human cells in vivo. Examples include:

Human cancer cells transferred into specialized mice help scientists study how cancers spread and uncover new anti-cancer therapies.

Mice engineered to have immune systems similar to humans allow scientists to study human immunity and autoimmune diseases and test new treatments for infectious diseases, including human-specific infectious diseases.

Human-mouse chimeras reveal how certain organs are diseased and how the resulting disease can be treated, for example studying human hepatitis virus infection and human-liver specific drug response in mice with human livers.

Mouse-human chimeras enable modeling stem cell replacement therapies to treat diseases such as diabetes or Parkinson’s.

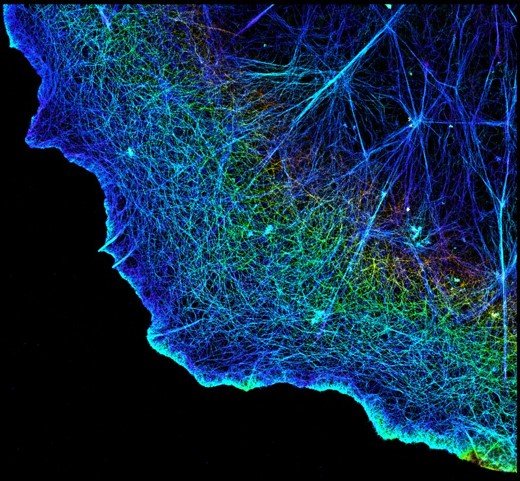

Chimeric mice with human neurons may identify treatments for devastating neural diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s diseases.

Shown from right to left are a mouse (black hair), rat (white hair), and a mouse-rat chimera (white and black hair). The mouse-rat chimera was made by injecting mouse pluripotent stem cells into a rat embryo. Mouse cells gave rise to cell types in the rat, including the black hair. Credit: Choi, 2017, Live Science.

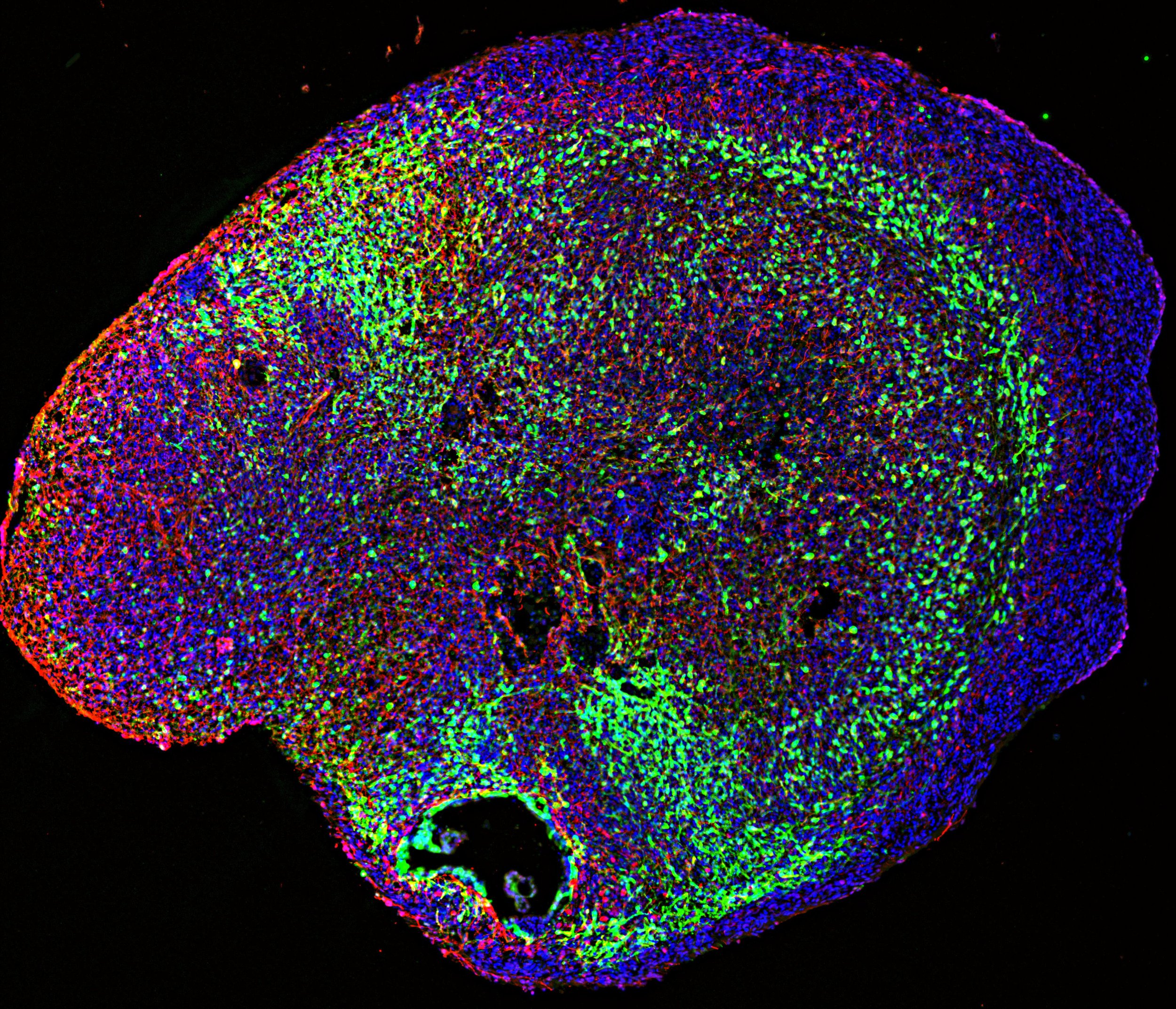

Another type of chimera research involves efforts to increase the supply of human organs for transplantation by developing the ability to grow human organs in animals. This involves the generation of chimeric organs in which human stem cells are added to animal embryos in a way that enables the formation of certain human organs, such as livers or pancreas, in animals. Studies using mouse-rat chimeras have demonstrated the feasibility of this approach to generate organs for transplantation. There are certain rat models that are unable to grow a pancreas. Mouse pluripotent stem cells transplanted into these rat embryos are able to generate the entire pancreas in these rats. Further proof of concept was demonstrated when cells from the rat pancreases could be transplanted back into mice with diabetes and reverse the disease.

What is the value of this research?

Scientists are in the early stages of chimera research, which is integral to biomedical research. Chimera research has the potential to greatly enhance our understanding of human development, help researchers improve model systems for identifying new therapies, and increase the supply of human organs for transplantation. Beyond the described benefits for cancer and immunology research, chimeras allow researchers to study how certain organs are affected by disease and how these diseases can be treated in a model that more closely resembles that in the human body without invasive procedures. Further, preclinical chimeric embryo research can evaluate the safety and efficacy of cellular therapies prior to going into patients, and potentially address the worldwide urgent shortage of human organs and tissues for transplantation.

What is the future of chimeric research?

The field holds significant potential for better understanding human development and creating new therapies. Chimeric research may uniquely identify new insights into human development, disease, and treatments that have the potential to help patients worldwide. Chimeric embryo research may one day generate human tissues in animals for transplantation to humans. There are currently more than 100,000 adults and children on the transplant waiting list in the United States and more than 150,000 on the waitlist in Europe. Each day, at least 17 people in these regions die waiting for a transplant. This research could lead to life saving transplant therapies in the future.

To ensure that chimeric research is performed ethically, the International Society for Stem Cell Research’s (ISSCR) Guidelines for Stem Cell Research and Clinical Translation state that chimeric embryo research that involves human cells should be subject to review and approval by specialized research oversight committees. The guidelines also prohibit the transfer of chimeric human-non-human embryos into the uterus of a human or certain non-human primates.