Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

Multiple sclerosis (MS) affects about 2.3 million people worldwide. Most people are diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 50, though disease onset can occur in young children and significantly older adults. MS presents in different forms, but generally it is a progressive disease, worsening over time. MS symptoms, their severity, and their progression, vary from person to person, and each person’s symptoms can change or fluctuate over time.

What is multiple sclerosis (MS)?

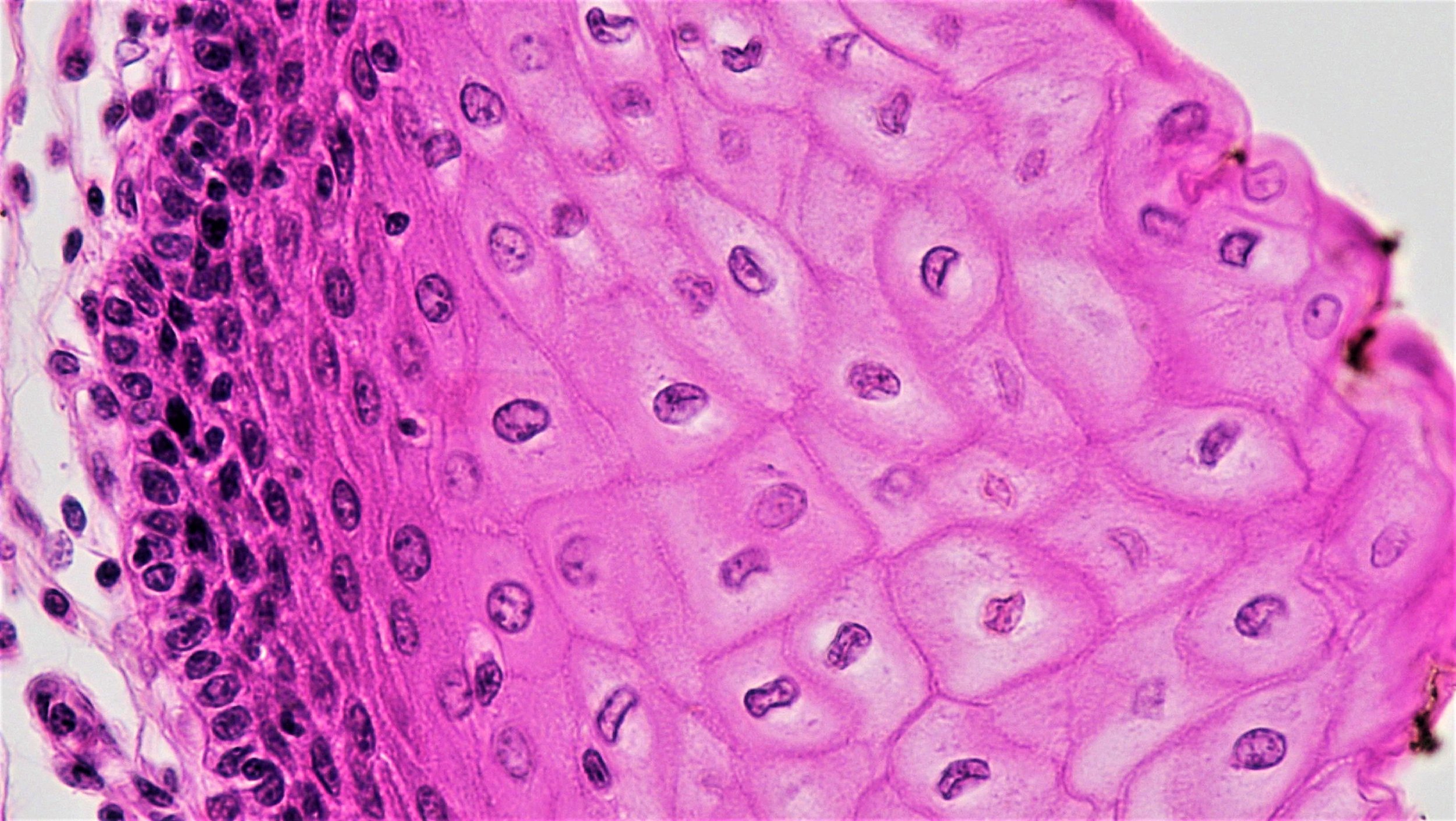

To understand MS, you must first understand the unique structure of neurons, the cells that allow us to move, balance, see, hear, taste, feel, remember and think.

The cell body of a neuron contains the nucleus and has a number of tentacle-like extensions, called dendrites, on its surface. A long fiber called the axon extends from the cell body and is coated with a protective sheath called myelin, which acts like insulation on a wire, protecting the axon and facilitating the sending and receiving of electrical signals. Myelin is generated by specialized glial cells, oligodendrocytes located in the brain and spinal column (the central nervous system), and Schwann cells in the network of nerves outside the brain and spinal column that connect it with the rest of the body (the peripheral nervous system).

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is thought to be an immune-mediated disease, most likely auto-immune, in which the immune system attacks the oligodendrocytes, causing damage to the myelin sheath. This damage interferes with the neurons’ ability to function properly and with time, results in direct damage to the neurons, resulting in permanent disability to vision, movement, and cognition. MS is one of the more common causes of neurological disability, especially in younger people.

People with MS may experience a wide range of symptoms, depending on which part of the brain and/or spinal cord is being affected, including blurred vision, pain, numbness, extreme fatigue, loss of movement and speech problems. MS is most likely caused by an interaction of several factors related to individual immunity, the environment, past infections (for example, viral or bacterial) and genetic predispositions, though no one knows for sure.

There are four main types of MS:

Relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS). This is by far the most common type of MS, accounting for about 85 percent of initial MS diagnoses. Patients experience clear attacks (or relapses) in which their motor skills or other neurologic functions worsen. Relapses are followed by periods of partial or complete recovery (remissions) in which symptoms partially or completely disappear.

Secondary progressive MS (SPMS). Most people who are initially diagnosed with RRMS will eventually move into this stage of the disease. MS will progress more steadily and patients may experience gradually worsening symptoms rather than sharp attacks, or they may experience both.

Primary progressive MS (PPMS). In PPMS, neurological function declines steadily from the onset of symptoms. This form of MS affects about 10 percent of all MS patients, and how quickly the disease progresses can vary widely. Some experience occasional plateaus in which symptoms neither improve nor worsen, and some experience short periods of minor improvement. PPMS typically does not have distinct relapses or remissions.

Progressive-relapsing MS (PRMS). This is the rarest form of MS, in which the disease steadily progresses from the beginning, with occasional flare-ups from which patients may or may not recover. There are no remission periods in PRMS. There are currently limited treatment options available for progressive MS, and none that effectively stabilize disease or restore lost function.

How is multiple sclerosis treated?

There is currently no cure for MS. Treatments for managing MS fall into two categories, those that mitigate symptoms and those that modulate the immune system.

Treatments that mitigate symptoms and help to maintain function include drugs that help with bladder control and irregularity, muscle spasms, tremors and pain, as well as exercise and physical therapy regimens focused on overall fitness and on addressing problems with mobility, speech, swallowing, memory and other cognitive functions.

Treatments that modulate the immune system include drugs developed to reduce disease activity and progression and to help with the management of relapses.

Many individuals with MS, and their family members, also benefit from psychological and social support, which is helpful in managing the stress related to life with an unpredictable and disabling illness.

How are we using stem cells to understand multiple sclerosis?

Researchers are studying stem cells to help them understand normal development of brain tissue, what goes wrong in MS, and to try to improve therapies. Neural stem cells (NSCs) from the central nervous system give rise to neurons as well as myelin-producing and support cells, oligodendrocytes and astrocytes, respectively. Neural stem cells are found in the fetal or adult brain and spinal cord.

NSCs can also be derived from two types of stem cells in the lab -- embryonic stem cells, which have the capacity to become any cell type in the body, or induced pluripotent stem cells, tissue-specific cells that are reprogrammed in the lab to behave like embryonic stem cells. Each of these pluripotent stem cells can be specialized to become neural stem cells which researchers can use to learn more about normal and diseased nerve cell function. Stem cells are enormously useful for learning more about the body’s natural repair mechanisms and for testing new drugs and treatments.

Scientists are using stem cells to:

Learn more about how myelin is normally maintained and repaired (a process called remyelination) and why this process sometimes fails;

Understand more about what causes MS;

Find ways to limit or prevent damage to neurons caused by the immune system;

Try to repair the damage by triggering or enhancing the body’s own repair or cell replacement mechanisms; and

Develop and test new treatments that can repair damage or stop the disease from progressing.

What is the potential for stem cells to treat multiple sclerosis?

There is exciting progress being made as researchers explore the potential of different types of stem cells to slow MS activity and to repair damage to the nervous system. There are no approved stem cell treatments for MS at this time, but there are various approaches being tested in clinical trials.

To prevent or reduce the damage done to nerve cells by the immune system, researchers are exploring ways to modulate what cells the immune system attacks or the intensity of its attack. One approach in clinical trials is to wipe out the patient’s immune system using strong doses of chemotherapy with antibodies and then use their own previously banked hematopoietic stem cells (blood forming stem cells) to regenerate the blood system. The goal of this approach is that the regenerated immune system will not attack the myelin or other brain tissue. While there is variation in patient response, it appears as if this process may “reset” the immune system, leading to the production of a new repertoire of immune cells, specifically T cells, which no longer attack the patient’s own cells. While this strategy may be curative, its risks limit its use to only the most severe cases of RRMS.

Another approach being tested in clinical trials is the use of a patient’s mesenchymal stem cells. These are isolated from stroma, or the connective tissue that surrounds other tissues and organs. Different trials are using these isolated stromal cells in different ways with the aim to dampen the individual's immune response and/or enhance repair of the damaged tissue, but the research has yet to reveal the role these cells play in immunomodulation.

Given the dearth of effective treatment options for the progressive myelin and neuronal loss of progressive MS, cell replacement is under investigation as a means of treating this condition. Neural stem cells can be grown in the lab to make glial progenitor cells that could replace oligodendrocytes lost during the course of MS. To that end, multiple groups have now transplanted glial progenitor cells to treat animal models of MS. Human and pluripotent stem cell-derived glial progenitor cells have significantly increased – and often rescued – the lifespans of mice with demyelination, with effective remyelination and recovery of lost neurological functions.

In the short-term, these cells are an excellent platform with which to screen for new drugs that might enhance intrinsic repair or resist damage.

What is the clinical status of cell-based therapies for multiple sclerosis?

The use of glial progenitor cells, which give rise to new myelin-producing oligodendrocytes, is under development as a potential treatment strategy, with the goals of stabilizing disease by preventing further neuronal loss and restoring function by remyelinating the demyelinated neurons. In preclinical work thus far, methods have been developed for producing large numbers of human glial progenitor cells from pluripotent human stem cells, including both embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. These cells have proven effective at remyelinating neurons in both young and adult animal models of demyelination. The potential use of stem cell-derived glial cells as cellular therapies for treating progressive MS is under review by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

We may reasonably anticipate that clinical trials testing glial progenitor cell-based therapies for progressive MS will progress in the relatively near future, pending acceptable preclinical safety data and FDA approval.

Useful Links

March 2019